The first day of 2017 I did my first flight of the year and already I am ticking off one box of my new year resolutions (which are ALL aviation related). I begun instrument flying for my 4 hours required to be a private pilot in Hong Kong! So here are the details of the flight:

We managed to start early, an entire hour early because my instructor's student simply forgotten that he had a lesson booked for today, presumably due to the alcohol and partying from New Year's Eve. But never mind that, it was awesome we can start early as we have quite a schedule for one hour. PFLs and Instrument Flying!

After a quick preflight, we got on and got started. We taxied out to the undershoot area for our engine performance check as another one of our 172s, B-LUW followed along, the aircraft was piloted by a well-known actor in Hong Kong and he was taking his two sons up for a New Year's Day ride, which is a great father and son(s) bonding activity to be perfectly honest.

We took off into the calm skies of this beautiful Sunday afternoon and departed the Shek Kong airspace via the Fire Station Gap, which gives us a perfect view of our neighbor city, Shenzhen. However, we quickly turned back into the training area and my instructor handed me the hood, time to "TRUST YOUR INSTRUMENTS HOWARD!"

The instructor remarked that my instrument flying was "An easy A grade, CPL standard." Well I did hold altitude within 50 feet and heading within 5 degrees, I must credit this performance for my first time flying under the hood to my numerous amounts of hours in FSX. However to any students wondering, yes you do feel the illusions as taught in human factors, and it does take practice to ignore it. I felt the sensation of the aircraft banking when in reality I was wings level, however I rectified it before the bank angle even exceeded 3 degrees. This is the thing about instrument flight is that if you spot a slight deviation, fix it there and then as a small deviation will very quickly exacerbate to a huge deviation. Also limit turns to no more than 20 degrees or around rate 1.

The Constant Aspect Forced Landing Technique:

After 20 minutes, I was cleared to use the actual horizon again and I took the hood off and we proceeded to do some PFLs, this is the fun part. Instead of doing the traditional square circuit with fixed "key" points, which if you are a pilot would probably be aware that it is on very rare occasions that you actually arrive at those points at the said altitudes. So it can be said that those altitudes are absolutely worthless. This is because there are many factors that come into account, such as wind and aircraft loading or even pilot technique! But the rules of thumb stays the same, maintain best glide speed, land into wind as much as practicable.

As the engine fails, the status quo remains, pitch and trim quickly for best airspeed as you look for the best field, preferably to the left and slightly in front, however do not limit choices to only that. I will not go into incredibly technical terms when it comes to field selection. Once the field is selected then you will first plan the general flight path and only then do the checks.

As I previously mentioned, the traditional way to execute and practice forced landings is by a square circuit with fixed key points with fixed altitudes, but in practice they are rarely met with any precision. This is why the Constant Aspect Forced Landing technique is a much safer and easier option. Consider the diagrams below:

|

| Credits to the Royal Air Force |

|

| Credits to the Royal Air Force |

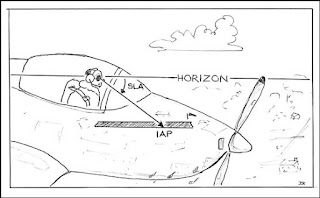

As shown on the diagram on the right, an IAP (Initial Aiming Point) is chosen which is around 1/3rd of the way down the selected landing site, and the idea is to fly a left circular pattern in order to keep the SLA (Sight Line Aspect) the same during the entirety of the circuit. This is not flown so you can maintain sight line but flown like this as it allows for better fine corrections and takes away all the complicated extrapolation and guesswork from the gliding descent. Note that one must maintain coordinated flight throughout the circular loop and also maintain the best glide speed as it will allow for the most ideal glide ratio.

As shown on the diagram below the previously mentioned diagram, the SLA Angle is the angle between the horizon and your sight line towards the IAP, and by eyeballing it should be around the neighborhood of 45 degrees so you wouldn't be too high or low. Note that while flying this technique the key positions and altitudes can be completely forgotten and your eyes should be 90% of the time looking out of the window. Basically it's like flying a straight in final approach, you keep this aiming point at the same point in your windscreen and this removes most, not all of the judgement calls you have to make during a traditional key position technique for forced landings.

The judgement calls the pilot still has to make is whether their SLA is too excessive (Aircraft too high, overshoot) or not significant enough (Aircraft too low, undershoot).

What if you are too high? First of all this is a more ideal position as it is easier to lose height than it is to gain the lost height when your engine has packed up. There are a couple of things in your power to do if this was the case:

- Widen out the circuit - Slacken your turns a little bit and wait for the SLA to correct itself.

- Use flaps - However be aware that premature use of flaps may cause a too low situation.

- On final, overshoot - Like the first technique.

- Slips - Great to lose a whole bunch of height, however proximity to Vso and the ground may be factors against such technique.

Most of the time, widening out and slacking the turns will be sufficient for the SLA to correct to a more ideal 45 degrees. Just note, the 45 degrees is just an eyeballed estimate like anything in flying, don't get out a protractor on your flight test!

Most importantly at the end of the maneuver, watch your altitude, don't get carried away with the oh so amazing glide approach thanks to the RAF. The minimum altitude according to the rules of the air is 500 feet away from any persons, structures or vessels. So remember to start climbing away at or before 500 feet to stay within the minimums!

So my advice now? Go up with an instructor familiar with this technique, or talk to your instructor about this technique and practice safely, use reasonable bank angles and watch your airspeed. Eventually you will find that you can use this technique in any sort of power off landing maneuver like a glide approach or for the Americans, the power off 180. This technique takes away all the nuanced effects of wind and load, and brings it all together with one simple rule: Keep the SLA constant, you will make it down alive. As the landing field is made, apply full flaps and complete your security checks.

How do you improve in the judgement of overshoot or undershoot? Well it all boils down to constant practice. So maybe this will be one of your New Year's Resolutions, to practice forced landings and be a better, safer, more competent pilot.

|

| My flight path yesterday |

So that's it for now, headset review coming up next!

Have fun, fly safe

--

Howard

No comments:

Post a Comment